Using high throughput computing to investigate the role of neural oscillations in visual working memory

July 6, 2022Jacqueline M. Fulvio, lab manager and research scientist for the Postle Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, explains how she used the HTCondor Software Suite to investigate neural oscillations in visual working memory.

If you could use a method of analysis that results in better insights into your research, you’d want to use that option. The catch? It can take months to analyze one set of data.

Jacqueline M. Fulvio, a research scientist for the Postle Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, explained at HTCondor Week 2022 how she overcame this problem using high throughput computing (HTC) in her analysis of neural oscillations’ role in visual working memory.

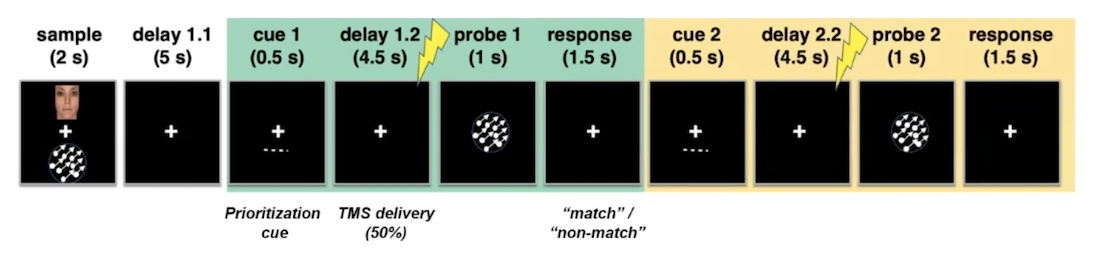

The Postle Lab analyzed the patterns of brain waves recorded from participants as they performed working memory tasks using an HTC workflow. Visual working memory is the brain process that temporarily allows us to maintain and manipulate visual information to solve a task. First, participants were given a sample with two images to memorize for two seconds. Then the image disappeared, and, following a five-second delay, participants were given a cue that indicated which item in memory would later be tested. The experimenter then delivered a single pulse of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to the participants’ scalp on half of the trials. TMS alters brain function, so Fulvio and her collaborators looked for corresponding impacts on participants’ brain waves recorded in an electroencephalogram (EEG). Finally, the participants indicated whether the image shown on the screen matched the original sample item.

After collecting and processing the data from the EEG, they can analyze the neural oscillations (or brain waves) to understand how they change throughout the task. Previous results have shown that the frequency of neural oscillations is associated with working memory processes.

“In our current work, we wanted to more deeply investigate the role of these neural oscillations in working memory,” Fulvio states, “we chose to leverage an analysis called spatially distributed phase coupling extraction with a frequency-specific phases model (SPACE-FSP).” This analysis is a multi-way decomposition of the EEG data.

The number of decomposable networks can’t be determined analytically, so the group estimates it using decomposition. Finding the optimal decomposition is an iterative process that starts with a statistical criterion and a set number of oscillating networks, which incrementally increase until they can no longer achieve the criterion. As a result, a single decomposition can take up to several months to complete.

Although this method provides better insight into what Fulvio and her group want to analyze, “this remains a largely unused approach in the field.” Fulvio speculates that other scientists in the field often don’t use this kind of analysis because it’s very computationally demanding. “This is where high throughput [computing] came in for us.”

Fulvio and her team planned to analyze at least 186 data sets, which, at the time, “seemed insurmountable.” The HTC capabilities of HTCondor offered them a solution to this problem by running the decompositions in parallel using the capacity of a campus wide shared facility. They also had the opportunity to utilize the Matlab parallel pool compatibility, which helped scale out the processing.

The group started following the HTC paradigm because their lab had already used services provided by the UW-Madison Center for High Throughput Computing (CHTC) for some time. Fulvio’s supervisor, Dr. Bradley Postle, suggested setting up a meeting and seeing if what they needed could be achieved using the capacity offered by CHTC.

Fulvio has an extensive coding history, but when she did run into compiling problems, she found the office hours offered by the CHTC Research Computing Facilitators extremely helpful, “I got useful tips from the staff in figuring out what was going wrong and what I needed to fix!”

The group ran 42 jobs, each job taking anywhere from two days to two weeks to run. The initial results of the analyses were promising, but the two data analysis pipelines the group tried were insufficient to address some of the critical questions.

After re-running the analyses using new data Fulvio collected, she overcame some limitations from the prior dataset to address the original questions. For this dataset, the group ran almost twice the amount of jobs – 72 – with each one again taking anywhere from two days to two weeks to run.

The group updated the analysis once more to increase the data size from 500 milliseconds to 1-second chunks. They also combined the data into a single pipeline instead of having it in different chunks of data for two separate analyses.

The goal of this update was to increase the amount of data they were sending, which in turn increased the amount of time it took to do these decompositions. More data resulted in a more robust and interpretable statistical result.

“All versions of the analyses were ultimately successful,” Fulvio comments. “We’ve benefited significantly from this process.” Their final analysis obtained 1,690 components – a “fantastic number” for their data analyses.

“We had such good support along the way so we could get this going,” Fulvio notes. In addition, what could have been years of computing on their lab machines, was condensed and boiled down into merely months for each analysis iteration.

The group also conducted one more analysis, as “[this] experience helped us think about a special control analysis,” Fulvio remarks. The group carried out hundreds of jobs within a day using this separate analysis, giving them rapid confirmation through the control analysis results.

Fulvio reflects, “from our research group’s broad perspective, OSPool capacity accessible via the CHTC have significantly expanded our computational capabilities.” Although computationally demanding, these resources helped the group apply this better-suited analysis method to address their original questions.

From a more personal perspective, Fulvio notes that learning how to take advantage of these OSPool capacity has improved her skills, including coding. These resources allowed her to work with additional languages and sharpened her ability to optimize code.

Fulvio concludes that “this has allowed us to help advance our field’s understanding, address key questions in the grant funding the research, and it provides the opportunity to reconsider other established findings and fill gaps in understanding of those studies.”

…

Watch a video recording of Jacqueline M. Fulvio’s talk at HTCondor Week 2022, and browse her slides.