High-throughput computing as an enabler of black hole science

May 12, 2022

On June 25, 2021, Arizona astrophysicist Feryal Ozel posted an item on Twitter that must have fired up scientific imaginations. She noted that the Open Science Pool (OSPool) just set a single-day record of capacity delivered — churning through more than 1.1 million core hours. Her team’s project was leading the surge.

“Can you tell something is cooking?” she asked cheekily.

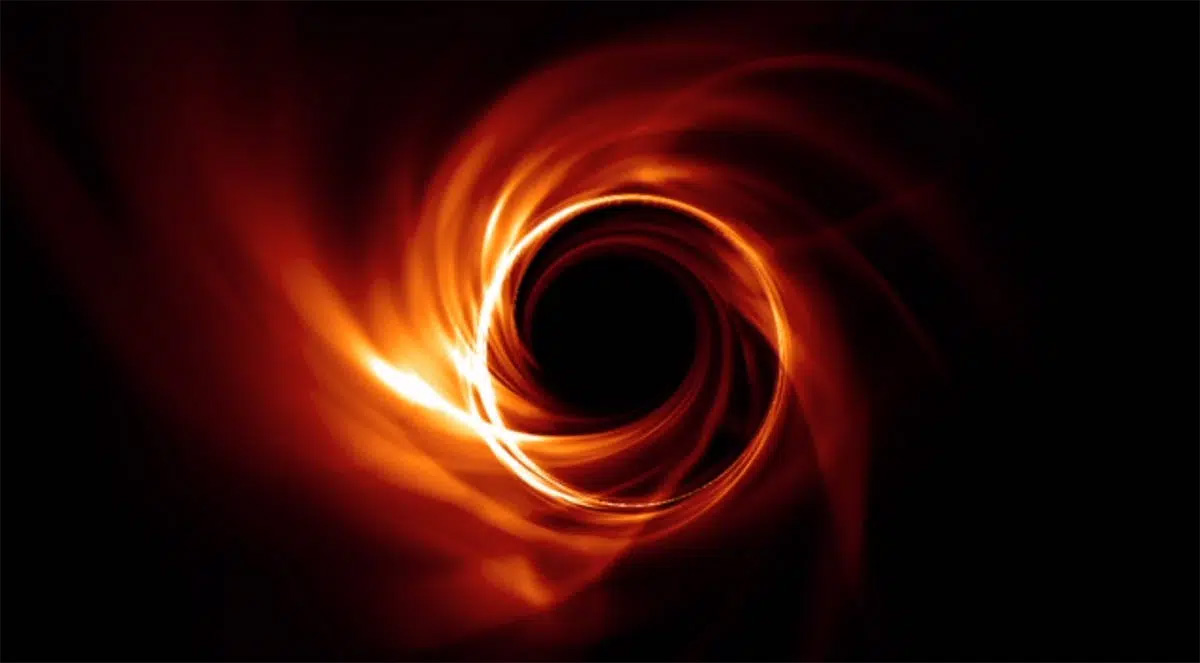

Almost a year later, the secret is out. The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Project, a collaboration of more than 300 astronomers around the world, announced on May 12 it had produced an image of a supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, only the second image of its kind in history.

EHT made that initial history in 2019 when it shared a dramatic image of a black hole at the center of the M87 galaxy, 55 million light-years from Earth, thereby taking black holes from a theoretical concept to an observable phenomenon.

For this newest image, EHT harnessed the power of the OSPool that is operated by the OSG Consortium to help with the computational challenge behind this work. This required the execution of more than 5 million computational tasks that consumed more than 20 million core hours. Most of the computations took place over a 3-month period in 2021.

Miron Livny

The OSG fabric of services has become the computational backbone for science pursuits of all sizes – from single investigators to international collaborations like EHT. Based on the high-throughput computing (HTC) principles pioneered by UW-Madison computer scientist and Morgridge Institute for Research investigator Miron Livny, the OSG services address the need of research projects to manage workloads that consist of ever-growing ensembles of computational tasks. Researchers can place these workloads at OSG Access Points and harness the capacity of the OSPool that is provided by contributions of more than 50 institutions across the country.

Over the decades, large international collaborations have been leveraging the OSG services to chase cosmic neutrinos at the South Pole, identify gravitational waves generated billions of miles away in space, and discover the last puzzle piece of particle physics, the Higgs boson.

Chi-Kwan “CK” Chan, a University of Arizona astronomer who coordinates the EHT simulation work, says the project uses data from 8 telescopes around the world. He says that since getting plugged into the OSG services in 2020, it has become a “critical resource” in producing the millions of simulations that help validate physical properties not directly “seen” by these telescopes — like temperature, density and plasma parameters.

“And once we pull together these many computed images across many parameters, we’re able to compare our simulations with our observations and develop a truer picture of the actual physics of a black hole,” Chan says.

“Simulation is especially important in astronomy, because our astrophysical system is so complicated,” he adds. “Using the OSG services allows us to discard hundreds of thousands of parameters and find the configurations that work the best.”

“It improved our science an order of magnitude.” – CK Chan

Chan adds that the OSG consortium also provides the storage the EHT simulation work needs, which allows data to exist in one place and makes it easier to manage. The bottom line is that OSG greatly improves the effectiveness of the EHT simulation work. Chan estimates that the partnership enabled the EHT scientists to accomplish in three months what might take 3 years with conventional methods.

“It improved our science an order of magnitude,” Chan adds. “There are so many more parameters of space that we can explore.”

The EHT collaboration was triggered through contacts at the National Science Foundation (NSF) Office for Advanced Cyberinfrastructure (OAC). “Following our commitment to leverage NSF investments in cyberinfrastructure, we reached out to CK and it turned out to be a perfect match,” Livny says.

NSF has been a vital supporter of the OSG Consortium since its origin in 2005, and this is a perfect example of a collaboration between two NSF funded activities, Livny says. In 2020, NSF launched the $22.5 million Partnership to Advance Throughput Computing (PATh), with a significant presence at the UW-Madison Computer Sciences Department and the Morgridge Institute for Research. That partnership is helping to expand the adoption of HTC and advance the HTC technologies that power the OSG Services.

Livny, who serves as principal investigator of PATh, says the EHT computational workload is the equivalent of having several million individual tasks on your to-do list. The HTC principles that underpin the OSG services provide effective means to manage such a long, and sometimes interdependent, to-do list. “Otherwise, it’s like trying to fill up a swimming pool one teaspoon at a time,” he says.

Chan and his team of researchers at Arizona, Illinois, and Harvard worked closely with the OSG team of research facilitators to optimize the impact of OSG services on their high throughput workloads. Led by UW-Madison facilitator Lauren Michael, the team provided the EHT group with the necessary storage, advised their workload automation policies, and helped them with moving results back to the Arizona campus.

Livny emphasizes that the OSG services are founded on the principles of sharing and mutual trust. Any U.S. researcher can bring their computational workload to an OSG Access Point and any U.S. institution can contribute computing capacity to the OSPool.

“I like to say that you don’t have to be a super person to do super high-throughput computing,” says Livny.

…

This article is courtesy of the Morgridge Institute for Research. Find the original article on the Morgridge Institute’s news page.

To read more about this discovery you can find other articles covering this event below: